7.1 Other mangrove studies

7.1.1 Alongi et al, 1992

“Nitrogen and phosphorus cycles”

Key contribution - This chapter is an overview of N and P cycles in mangroves from the Tropical Mangrove Ecosystems book.

Nitrogen

The various pools of N in mangroves are characterized as follows:

- Waters - Dissolved organic N (DON) is primary form of N in mangrove ecosystems. Dissolved inorganic N is relatively low, with most of the inorganic form represented by ammonium and lesser amounts of nitrate and nitrite. Relatively little temporal and spatial variation in DON due to refractory nature of DON.

- Sediments - Dissolved inorganic N is low in mangrove sediments, whereas DON is high; In general rates of ammonium uptake by mangrove trees exceeds regeneration rates.

- Adsorption of ammonium to sediments has been shown to be low in silt-dominated sites

- Concentrations of total extractable N vary with sediment type and are correlate with distributions of fine roots (often highest at 20-40 cm interval)

Transformation of N

Bacterioplankton activities are believed to be major pathway of organic N transformation to ammonium, but as of 1992 the process had not been quantified.

Immobilization (reincorporation of N into biomass) is primarily driven by the C:N ratio of decomposing organic matter. Given the relatively high C:N ratio of mangrove tree litter biomass, likely have significant rates of N immobilization within sediments.

Nitrification - occurs close to sediment-water interface in oxidized linings of animal burrows or the rhizosphere. Performed by microorganisms; Nitrate is relatively short-lived in soil environment as it is taken up by plants or involved in other chemical reactions.

Dissimilatory nitrate reduction - process in which nitrate serves as the electron accepter in respiration of anaerobic bacteria (reduced to nitrite). The reduction of nitrate to nitrite in mangroves is significant, and an additional step that results in reduction of nitrite to ammonium occurs (see Fernandes 2012).

Denitrification - conversion of nitrate to N2 and N2O gases occurs, but may be most prominent in polluted sites.

N fixation - carried out by bacteria and cyanobacteria; cyanobacterial mats on exposed sediments or associated with AG roots are primary location of N-fixing activity. Rates of fixation largely related to abundance of cyanobacteria

Phosphorus

Pools of P

Waters - dissolved organic and inorganic P are low in mangroves; dissolved inorganic P exists primarily as a salt HPO42-. Availability of P in waters may be either dissolved in water column or bound to sediments in highly depositional settings.

Sediments - Limited data as of 1992, but results indicate low dissolved P availability; total concentrations are relatively high however given high organic matter contents. - although organic P is largest pool, inorganic P is most readily available pool; most is bound in form of Ca, Al, or Fe phosphates - organic pools represent influence of roots whereas inorganic pools (mostly Fe-P) increase with depth as result of anoxia

Transformation

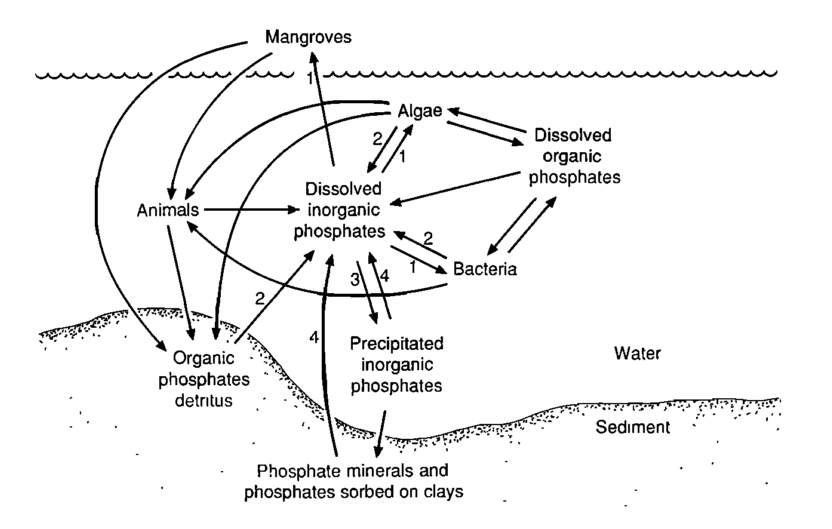

Transformation of P can be described primarily as biotic (assimilation, excretion, hydrolysis) or abiotic pathways (precipitation, adsorption and chemisorption, and dissolution and desorption)

Kaolite clays are particularly efficient at absorbing phosphates and thus precipitation of phosphates with Ca, Fe, Al, or clays results in large removal of soluble phosphates to the mineral pool.

A diagram of the Phosphurus cycle in mangroves is shown below:

Uptake by organisms - bacteria, algae, and higher plants take up dissolved orthophosphate or organic phosphates (which may alternatively be hydrolyzed first)

Sediment/water exchange of P & N

Little empirical work has been performed on this as of 1992, but data indicate that fluxes from the sediment (benthos) to water (pelagic) systems is small.

Detritus decomposition

Majority of detritus in mangroves is from within the system. Important considerations for decomposition of mangrove detritus are:

- High content of lignocellulose results in relatively slow decomposition

- Avicennia litter decomposes quite quickly as it is more nutritionally available

- Nitrogen is almost entirely conserved (100% concentration) of original litter during decomposition

- Occurs through different phases: loss of water-soluble compounds, microbial colonization and utilization, and mechanical fragmentation

7.1.2 Farnsworth, 1998

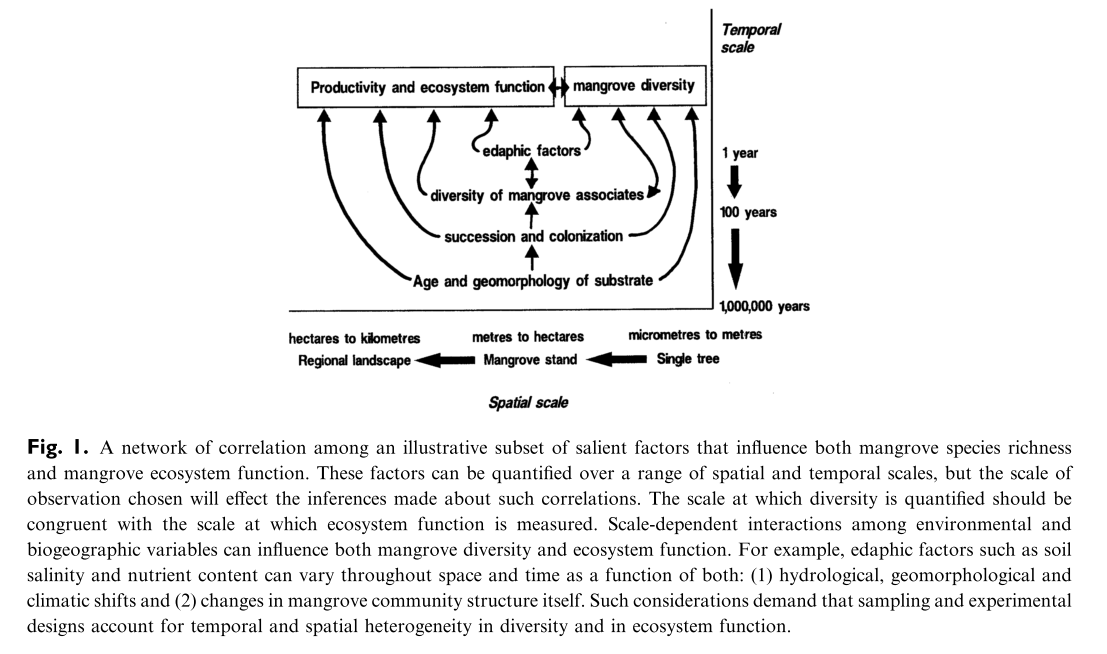

“Issues of spatial, taxonomic, and temporal scale in delineating links between mangrove diversity and ecosystem function” (Farnsworth 1998)

Key contribution: This review examines the linkages between species diversity and ecosystem functioning at different spatial and temporal scales, and discussing the implications on appropriate research designs & approaches.

Key notes: There are a number of relevant points in the paper, but of particular interest is the section entitled “Heterogeneity among mangrove communities – variation over tens of kilometres”.

In particular, this section has relevance for the RSE paper with Iryna, as the author discusses analyses of spatial geometry for better understanding processes and functioning within mangrove systems. She cites several studies that may be of interest for looking into further:

- MacArthur & Wilson, 1967 - The theory of island biogeography

- Burrough, 1983 - Multiscale sources of spatial variation in soil. I. Application of fractal concepts to nested levels of soil variation

- Krummel et al 1987 - Landscape patterns in a disturbed environment

- Kolasa, 1989 - Ecological systems in hierarchical perspective: Breaks in community structure and other consequences

- Holling, 1992 - Cross-scale morphology, geometry, and dynamics of ecosystems ***

Furthermore, the author notes that mangrove are particularly well-suited to such analyses, as component species are easily distinguished and mapped at multiple scales, and “islands of a wide range of sizes, shapes, and species composition are available for study.”

A nice conceptual diagram of different ecosystem processes in mangroves across different scales is provided:

Much of the paper focuses on different spatial scales, but they also note the importance of temporal scales at the end, with particular emphasis on the importance of defining the appropriate boundaries for the study of interest at a given time.

## Pseudoreplication

7.1.3 Hurlbert, 1984

“Pseudoreplication and the design of ecological field experiments” (Hurlbert 1984)

Key significance: This seminal article outlines the risks of pseudoreplication in ecology, with specific examples from the literature.

Key notes: The five key steps of the research process are:

- Hypothesis formulation

- Experimental design

- Experimental execution

- Statistical analysis

- Interpretation

Experimental execution is highly prone to induced errors from systematic bias, and are an important component of assessing the validity and quality of an experiment.

Experimental design is defined as the “logical structure of the experiment”.

Hurlbert outlines two different classes of experiments:

- Mensurative experiments - involve making measurements at one or more points in space and time, and thus “space” or “time” is the only “experimental” variable or “treatment”.

- Assuring replicate samples or measurements are dispersed in space (or time) in a manner appropriate to specific hypothesis is most critical aspect od design of a mensurative experiment

- Pseudoreplication often a consequence of actual physical space over which samples are taken being smaller or more restricted than inference space implicit in the hypothesis being tested.

- Manipulative experiments - always involves two or more treatments, and has as its goal the making of one or more comparisons. Different experimental units receive different treatments and assignment of treatments to experimental units is or can be randomized.

- Pseudoreplication most commonly results from inferential statistics on experimental design in which treatments are not replicated, or replicates are not statistically independent.

Pseudoreplication as Hurlbert defines it is “the testing for treatment effects with an error term inappropriate to the hypothesis being considered.” Thus, it is a combination of experimental design as well as analysis that results in the issues (improper design and analysis pairing).

Critical features of controlled experiments

Hurlbert outlines 6 potential sources of confusion in controlled experiments:

- Temporal change

- Procedure effects

- Experimenter bias

- Experimenter-generated variability (random error)

- Initial or inherent variability among experimental units

- Intrusion - either potentially foreseen or chance events that impinge upon an experiment in progress; chance events occur in all experiments and add to “noise”

- replication and interspersion of treatments provide the best insurance against chance events

Primarily four critical features of experimental design reduce the influence of these sources of confusion: controls, replication, randomization and interspersion.

Randomized block design

Allows for insurance against non-demonic intrusion as the block design explicitly introduces a certain degree of interspersion. Block designs may look like 4 different blocks with two plots in each block, and one of two treatments assigned randomly to one plot in each block.

Systematic design

May be helpful in mandating interspersion so long as cyclical variation in environmental variables does not co-occur with the systematic layout.

Randomization vs. interspersion

Argument largely held by Fisher and Gossett over randomized versus systematic layouts within experimental designs. Fisher maintained that interspersion was a secondary concern and should never be pursued at expense of exact knowledge of alpha.

Prelayout alpha - probability, averaged over all possible layouts of a given experiment, of making a type I error (false positive) Layout-specific alpha - probability of making a type I error if a particular layout is used

The issue is that the layout-specific alpha is of primary concern given the presence of only one experimental design in most cases, and yet it is never exactly known or specified.

Depending on the degree of interspersion and environmental gradients, layout-specific alpha will relate to the prelayout alpha in a predictable manner (less dispersion, LS alpha > PL alpha; more dispersion, LS alpha < PL alpha). Typically want PL alpha (the specified criteria) to act as an upper bound on LS alpha.

Statistical consequences

Simple pseudoreplication is the most fundamental form of pseudoreplication and refers to the case in which replicates are considered within experimental units rather than as individual experimental units.

In using replicates from within an experimental unit, one erroneously increases the degrees of freedom and reduces the variance (as additional samples from within a unit will come to more fully represent that unit) of statistical analyses. This makes it much easier to falsely reject the true null hypothesis (Type I error; false positive).

References

Farnsworth, Elizabeth. 1998. “Issues of Spatial, Taxonomic and Temporal Scale in Delineating Links Between Mangrove Diversity and Ecosystem Function.” Global Ecology & Biogeography Letters 7 (1): 15–25. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.1998.00265.x.

Hurlbert, Stuart H. 1984. “Pseudoreplication and the Design of Ecological Field Experiments.” Ecological Monographs 54 (2): 187–211. doi:10.2307/1942661.